The world has changed thanks to generative AI models like ChatGPT. These models are highly applicable to fields like copilots and agent AI, but their future in EDA (electronic design automation) tools remains unclear. So, what are the right applications? Can AI make EDA tools faster and better?

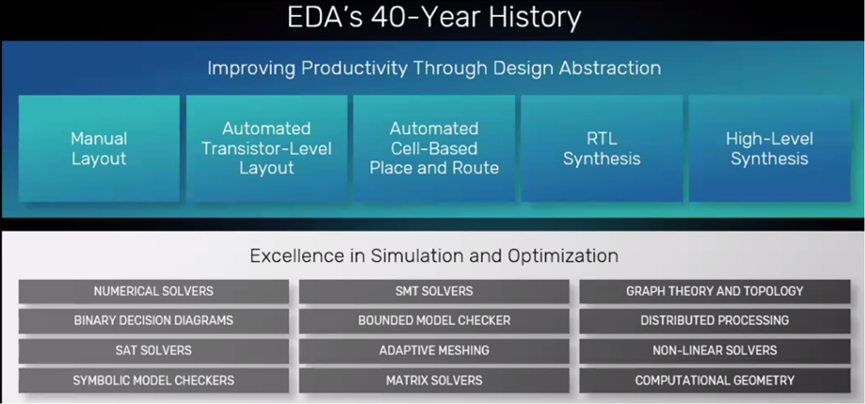

For the past 40 years, EDA has been driving Moore's Law, which requires constantly pushing the boundaries of many developed algorithms and technologies (see Figure 1). In some cases, the algorithms may already exist, but the computing power has been insufficient to make them practical. This is also true for AI-based solutions.

"This isn't a new journey for EDA," said Rob Knoth, director of strategy and new business units at Cadence. "It's something we've been working towards for decades. With every technological advancement, engineers have eagerly embraced automation. Without it, they simply wouldn't be able to get home in time for dinner with their families. With each generation of technology, the workload and complexity are exponentially increasing."

Figure 1: The evolution of EDA and algorithms. Source: Cadence

The use of AI within EDA is not new. One of the earliest developers was Solido Solutions (now part of Siemens EDA), founded in 2005, long before the advent of generative AI. The company used machine learning techniques, and there are other examples based on reinforcement learning. "Early tools focused on getting better design coverage with fewer simulations, rather than brute-force methods," says Amit Gupta, vice president and general manager of the Custom IC Division at Siemens EDA. "Those are applications that make a lot of sense within the tools themselves."

Many other tools followed suit. "Think about all the technology we've released in the last five years," says Anand Thiruvengadam, senior director and head of AI product management at Synopsys. "It started with optimization techniques based on reinforcement learning."

Each company adopted the techniques they found useful. "We leveraged planning algorithms," says Dave Kelf, CEO of Breker Verification Systems. "This is a widely used agent-based approach that adds intelligence to state-space exploration during test generation, going beyond simple random decision-making."

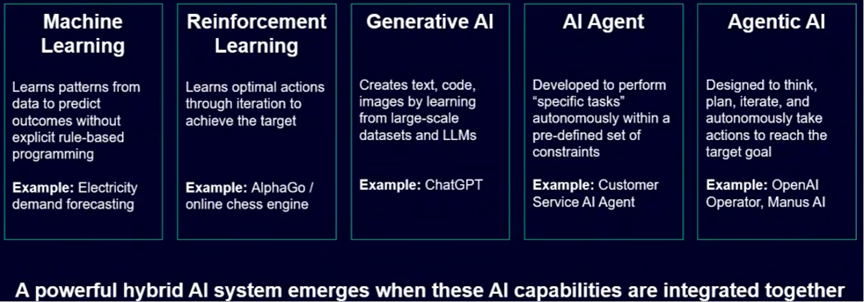

Just over two years ago, however, AI's perceptual capabilities took a quantum leap, fueled by explosive growth in computing power. Generative AI became accessible, and more recently, tools and platforms for implementing agent-based AI have been introduced (see Figure 2). While there may be questions about its economic benefits, the growth of computing power shows no signs of slowing down.

Figure 2: Categories of AI and their use cases. Source: Siemens EDA

However, these advances don't mean every new technology is superior to existing ones. "Don't forget the underlying math," said Cadence's Knoth. "AI is an amazing technology, but using it in isolation isn't always the most efficient or precise way to get an answer. If you have the math and physics to describe a system, computing the answer is an incredibly efficient and precise way to work. AI can help accelerate that process. AI can learn from our computations. But you can't give up those first principles. You can't give up truly understanding the domain, because that's the real superpower. The real magic happens when you think about how they reinforce and help each other."

Most EDA tools are still rules-based. "You still have to deal with some end goal and some end constraint," said Michal Siwinski, chief marketing officer at Arteris. "Within this framework, AI will exist both inside and outside the tool. Both are necessary, but they will behave differently. This question about AI was answered at the beginning of this century, given that many tools already have AI internally and are demonstrating consistently good and reliable results. Since then, we've only been refining and improving it."

The Unique Needs of EDA

The high cost of failure in any chip design means accuracy and verifiability are two highly sought-after features in EDA tools. "They don't want AI to be a black-box solution that spits out an answer and then you're not sure if it's correct," said Siemens' Gupta. "You want transparency and clarity in how it arrived at the solution so it can be verified. It needs to be able to handle a wide range of design problems, not just specific cases, and it needs to be generally robust."

When dealing with optimization problems, correctness is a much easier issue to address. "Reinforcement learning-based optimization techniques are essentially designed to help with this problem," said Synopsys' Thiruvengadam. "Typically in chip design, you're faced with a very large design space or optimization space, and you have to have an efficient way to explore that space to arrive at the correct solution, the best answer, or the best set of answers. This is a very difficult problem. That's where AI can help."

Design optimization can improve engineer productivity. "It helps make an engineer incredibly efficient at the subsystem level," said Knoth. "This helps port a successful 'recipe' for one module to another. It's about the hard work of delivering better PPA (power, performance, area) in a short period of time without a significant new engineering investment. This isn't using large language models. It's using reinforcement learning. You can't just get distracted by the latest 'shiny' thing. It's about building on and mastering the 'excellence' you've built over decades."

Applying the wrong model to the problem is where the trouble begins. "Many incumbent companies, frustrated with AI technology, are essentially just wrapping generic GPT models into vanilla LLM calls," said Hanna Yip, product manager at Normal Computing. "They don't understand the specific context and codebase that design verification engineers work in. This leads to hallucinations and a loss of context, which is fatal in chip verification. AI needs to leverage more than just these basic models. Formal modeling and agent-based methods within the codebase are the right approach."

The scale of the problem exceeds the capabilities of some commercial products. "We're not simply taking off-the-shelf AI, open source algorithms, and applying them to EDA," said Gupta. "Instead, we think about the scale of the problem we're dealing with. We're talking about seven process parameters per device, coming from the foundry. We're talking about millions of devices. We're talking about a massive dimensionality problem. The tools also have to be able to understand the different modalities that exist in EDA. There are schematics, waveforms, Excel spreadsheets, and they have to understand both the chip design and the board design."

Even with the new approach, the goal hasn't changed. "You still have decision trees within each technology," said Arteris' Siwinski. "Within that, you can replace some of the 'dumb heuristics.' Can you do better with reinforcement training? Or use AI techniques to do better clustering and classification to do some of the analysis upfront? There are 'dumb' analysis methods and there are 'smart' analysis methods. Can we ensure that the heuristics within all technologies get better and continue to improve? The short answer is yes. Almost all modern tools do this to some extent, because you're just changing the type of algorithm and the type of math that's being used to perform the task. Whether it's design, verification, or implementation, you're just changing the algorithm."

There are good things, and there are some bad things. "You need data to train the models," said Rich Goldman, director of Ansys, now part of Synopsys. "This gives the incumbent IC design companies and the incumbent EDA companies a huge advantage. This will make it harder for startups to get involved in creating EDA tools. It will be harder for them to get that advantage from the models. There will be some general-purpose models and big language models that they can leverage, but not to the extent that the incumbents can because they have the data."

Trust is a key challenge in using AI tools

"Signoff is about trust," said Knoth. "Accuracy plays a huge role, but it's really the trust that's built up over time, over generations of technology, proving that when I get this number out of the system, I can safely make a decision based on it. That's a very important part. Computation is the foundation for that trust; a rough understanding of how the tool operates gives you a sense of how it will respond when faced with something it hasn't seen before."

Transparency is key to trust. "Current AI solutions are just black boxes," said Prashant, a product manager at Normal Computing. "There needs to be a way to generate collateral to make the AI's reasoning visible. This can be achieved through formal models, ontologies, and linked test plans, so that design verification engineers can clearly see how the tool's output maps back to the specification. This explainability is fundamental to building confidence in AI, especially in a high-trust environment like chip design, where you need to be confident that this isn't just the output of a black box."

Tools need to explain how they work. "When we're working on four, five, or six sigma problems, we plot an AI convergence curve," said Gupta. "The user can then see what the AI is doing. It does some model training and starts looking for those six sigma points. It predicts the worst-case scenario and runs simulations against that point to verify. Then it finds the second worst-case scenario, the third worst-case scenario. In some cases, it might get it wrong, but then it reruns some training underneath to build a more accurate model. This is an adaptive model training method that continually improves until it has enough confidence to find all those outliers. Even then, there might still be one or two it missed, but it's much better than manual methods, which require running hundreds of simulations and extrapolating. It's getting close to being almost as good as brute-force."

One concern in the industry is hallucinations. "When I hear people talk about AI hallucinating, I just see it as a 'garbage in, garbage out' problem," said Siwinski. "It's just math. When we use this technology in the industry, we have to make sure the training dataset we feed it is correct. Otherwise, we might get the wrong answer. It needs checks and balances. You can't just give it anything. In the consumer world, you can have AI create crazy images based on whatever's available. That's an extremely unconstrained problem. When using AI in our field, we're less prone to hallucinations."

Don't expect one tool to solve all problems. "The hardware needs to be consistent across the entire system," said Arvind Srinivasan, head of product engineering at Normal Computing. "You can't generate one part in isolation and expect it to make sense as a whole. This is very different from language, where you can write a paragraph on your own. Furthermore, the data volume is insufficient. We don't have trillions of examples. Even within a company, IP is locked in silos. You can't just do supervised learning. You need algorithms that can incorporate prior data about system constraints and learn from that data. Labeling is expensive. You can't pay a chip engineer a six-figure salary to annotate a training set. Without ground truth data, validating AI results requires deep industry expertise, making evaluation much more difficult than in the consumer space."

Sometimes you need AI to break the mold. "AI technology allows us to tackle more ambiguous problems," said Benjamin Prautsch, group manager in the Adaptive Systems Engineering department at Fraunhofer IIS. "But at the same time, the results are more ambiguous. Therefore, careful scrutiny and testing are essential. Positive user experiences and visible evidence are key. For example, validation tools are considered 'golden tools,' and that's the market's view. Only a strong track record can convince people, and that remains to be proven."

But sometimes you want AI to think outside the obvious box. "AI is very good at checking or removing bias, and you can give it more freedom," Siwinski said. "It still has to follow certain rules, and you still have to meet certain performance requirements, so you can't do whatever you want. But once you do, can you get the AI to give you a different answer than the one the experts created? You want to see that creativity within certain constraints. You want to explore a wider design space, and sometimes it will find a different and better answer because the engineers made certain assumptions based on their best past experience. Those assumptions are valid, but that doesn't mean they're the only way to achieve something."

Value creation comes in more than one form. "People don't use AI tools because they're always right," said Yip of Normal. "They use them because they save a lot of time compared to traditional methods. The real challenge is ensuring engineers don't waste time reviewing bad outputs and providing them with the right tools to check and fix them. The framework here should be, 'Does it save engineers more time than the time required for review?' If the answer is yes, it earns trust."

Existing tools haven't fully earned trust either. "Silicon engineers don't inherently trust existing EDA design tools beyond very basic functionality," said Marc Bright, silicon director at Normal. "We spend a lot of time running other tools and writing our own tools to check the quality of their output. When AI tools reduce the effort and time required to generate these outputs, we can spend more time evaluating and refining potentially better solutions."

Insufficient data is a barrier to AI learning. Part of the problem is that AI doesn't have enough examples to learn from. "Low propensity languages are those for which there's insufficient data and resources for effective natural language processing," said Knoth. "If you ask AI to write a document in English, it has already been trained on a massive corpus of English. So if you ask it to generate technical specifications, that's something the AI already has a lot of data to draw on. If you ask a large language model to generate C code, that's also credible. The amount of training data is smaller, but there's still a lot of publicly available C code, and there are ways to verify the generated code. Let's look further down the list - the amount of public training data for Verilog is only a fraction of that for C code. Look further down the list - Skill, TCL, UPF. Our industry is saturated with these languages, and the amount of high-quality, publicly available data to train models is a challenge. Every company that deploys these technologies has a sizable treasure trove within their organization, but applying this proprietary IP to large language models in a computationally efficient manner is not easy."

Source: Content compiled from semiengineering